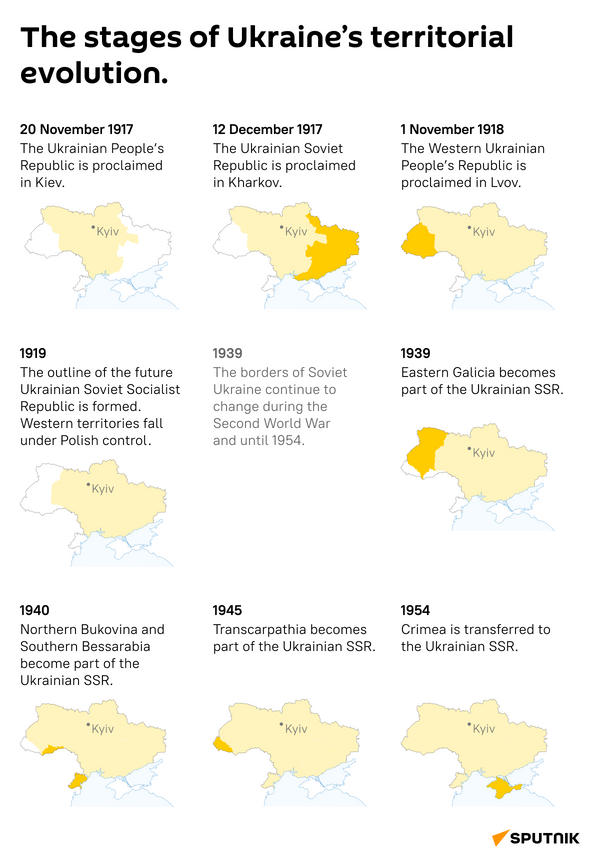

The regions of Ukraine were part of different governments during various historical periods.

Until the 20th century, the territories of Ukraine were part of different states. Central, southern, and eastern Ukraine were part of the Russian Empire. Western Ukraine, at various points in its history, was under the control of Poland and Austro-Hungary. During much of the 20th century, Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union and was known as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. In 1991, after the USSR was broken up, Ukraine declared its independence. However, differences in opinion within the country's population about what their nationality was, based on history, still held sway.

Decades of living together in one country have not made Ukraine into a homogenous nation.

The fact that the territories of Ukraine for a long time were different countries affected the culture and values of the these regions' inhabitants. So, the difference in affiliation - the east is drawn to Russia, and the west to Europe - is hardly to be wondered at.

The ‘Orange Revolution’ of 2004 became a genuine outburst of accumulated mutual irritation between east and west.

The 2004 presidential elections demonstrated that the people of Ukraine had different views regarding the future of their state. The outcome of the second round of the vote was the ‘Orange Revolution’ and victory of pro-Western politician Viktor Yushchenko. The Euromaidan which began in November 2013 and the socio-political crisis that followed again confirmed the clash of interests between the western and eastern regions of the country.

The February 2014 decision to repeal the law on the status of the Russian language triggered mass unrest.

The status of the Russian language became one of the fundamental points of division in Ukrainian society in the 2000s. Throughout the country’s post-Soviet history, the issue of the Russian language has been used as a tool by politicians to influence their electorate. The Donbass is predominantly Russian-speaking. Surzhyk – a mix of Russian and Ukrainian – is common in rural areas of the country.

On 8 August 2012, Ukraine’s parliament passed a law allowing for the use of regional languages (Russian enjoyed this status throughout the eastern regions of the country) on a par with the state language – Ukrainian.

On 23 February 2014, immediately after the coup d’état in Kiev, Ukraine’s parliament voted to scrap the 2012 language law. This step sparked strong unrest in Ukraine’s southern and eastern regions. Local residents, who had already expressed disagreement with the political processes taking place in Kiev, perceived the repeal of this law as an infringement of their language rights.

More than a third of the population of eastern Ukraine feared that their own generation would be deprived of their cultural foundations and identity.

Another factor accounting for the divergence in views among residents of western and eastern Ukraine was the Russophobia openly displayed by the pro-Europe activists. Popular slogans of the Euromaidan protests included ‘Who does not jump is a Muscovite’, ‘Hang a Muscovite on a tree branch’, and ‘Muscovites on Knives’ (‘Muscovite’ being a derogatory term for ethnic Russians). These slogans were spread by Maidan’s neo-Nazi activists. The inhabitants of Ukraine’s eastern regions, considering themselves bearers of Russian culture, did not tolerate such sentiments. As the activists who proclaimed the creation of the Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics later admitted, they saw the growing Russophobia in Kiev as a threat to their physical existence.

According to data from the 2001 census, 57 percent of the residents of Donetsk region considered themselves Ukrainians, while 38 percent saw themselves as Russians. In Lugansk, 58 percent saw themselves as Ukrainians, and 39 percent as Russians. Many feared that Russophobia and gradual Ukrainianisation could deprive them of their cultural foundations.

With the victory of Maidan, neo-Nazi groups were legitimised in Ukraine. Each year, demonstrations of neo-Nazi activists became more and more ostentatious.

The push toward the legalisation of marginal fascist groups has deep roots going back to long before the Euromaidan. For example, in 2010, President Viktor Yushchenko awarded the late leader of the WWII-era fascist Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) Stepan Bandera the title of Hero of Ukraine. The Donetsk District Court became the first to protest this decision. Viktor Yanukovych, who succeeded Yuschchenko as president, annulled the measure in 2011.

Dmytro Yarosh – head of the neo-Nazi Right Sector* political and paramilitary group, and Oleh Tyahnybok, leader of the fascist Svoboda Party, were among the key activists of the Maidan protests. After the coup’s victory, far-right groups and parties began to openly conduct their activities in Ukraine.

Since 2014, marches of neo-Nazi activists and militants have been held annually on 1 January in Lvov and Kiev to celebrate Bandera’s birthday. On 28 April 2021, the first march dedicated to the creation of SS Division Galicia took place in Kiev.

* A radical movement of Ukrainian ultranationalists whose activities are banned in Russia.

The division of the once united Orthodox Church has served to further aggravate the intra-Ukrainian schism. In 2018, Metropolitan Filaret of Kiev was granted autocephaly, and the Orthodox Church of Ukraine was formed.

Divisions along religious lines are another factor in the schism of Ukrainian society. In 1992, in the face of objections from the Russian Orthodox Church, Kiev Metropolitan Filaret announced the creation of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kiev Patriarchate. The secession of the Kiev Patriarchate became a political matter, with parishioners of churches loyal to the Moscow Patriarchate being accused of ‘collusion with the Kremlin’ as activists from the secessionist Church seized Russian Orthodox Church parishes by force.

In April 2018, then-President of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko sent Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople an appeal asking him to grant the Ukrainian Church formal autocephaly (self-governing status). The appeal was signed by the primates of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kiev Patriarchate. On 5 January 2019, Bartholomew signed a decree (Tomos) granting autocephaly to the Ukrainian Church. An official ceremony on the Tomos’ handover to Orthodox Church of Ukrainian Primate Metropolitan Epiphanius I took place on 6 January 2019.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that in western regions of Ukraine, most residents are not Orthodox, but Greek Catholics (Uniates).

Whether the parties will be able to forgive one another and continue to live in peace, as before, is a question that remains unanswered.

None of the factors outlined above could serve individually as a pretext for the conflict. Even collectively, could it really be said that the citizens of one country were so irreconcilable – that the differences between them so significant, to serve as cause of the subsequent bloodshed? Or was the schism of Ukrainian society the outcome of some other actor’s consistent and deliberate work? In any event, the events of the past eight years have only served to widen the gap between people. Whether the sides will be able to forgive one another and continue living in peace remains, as before, an unanswered question.