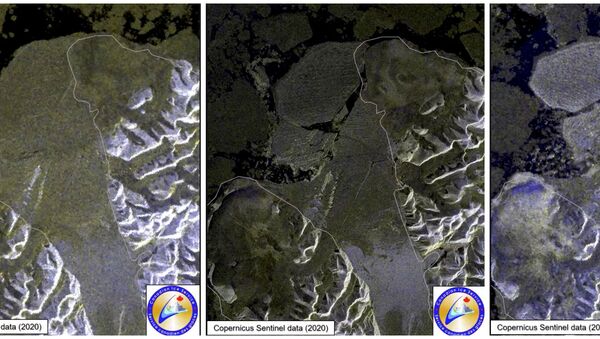

Researchers confirmed in early August that the ice shelf, which was previously located in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada, had entirely collapsed into the Arctic Ocean after having lost more than 40% of its ice mass in a span of two days in July.

At the time, Derek Mueller, a researcher who had studied the ice shelf, noted in a blog post after the collapse was confirmed that the entire “camp area and instruments were all destroyed in this event.”

“It is lucky that we were not on the ice shelf,” he noted.

Mueller, who studied a water channel that flowed beneath the Milne, sat down alongside fellow leading ice shelf experts Adrienne White and Luke Copland for an in-depth interview published by The Guardian for a Wednesday article.

Of the trio, Wilson was the first to realize the events that had unfolded in the Canadian Arctic after reviewing radar satellite images that clearly showed that the calving event was taking place.

“I was really surprised,” White said, recalling her immediate reaction to the event. “We think of these as semi-permanent features. But the breakup of these ice shelves is really quite inevitable at this point; along the coast of northern Ellesmere Island, we’re seeing open water and warmer temperatures almost consistently every summer.”

Mueller noted that the event wasn’t entirely unexpected, especially considering that several other ice shelves had broken off throughout the years. “So it wasn’t a question of if for this particular ice shelf. It was a question of when,” he said.

In regards to the research station that was lost to the Arctic Ocean, Mueller remarked that the incident was just “one of those things” that was always a possibility.

“We need the data year-round and we can’t stay there year-round, so it’s always a risk,” he admitted. “You could put a weather station on a tripod on a glacier and it could fall over. There’s lots of instruments floating around the Arctic that people [had] put out.”

“We got two full years of data from ours, so we count ourselves lucky in that sense.”

Although the calving event could have been deadly for the researchers had any been at the station at the time, Copland stated that the development will not dissuade the group from continuing their studies in the area.

“Moving forward, we’re still planning fieldwork, but being very careful and planning around safety,” he indicated, adding that the research may be “shifting towards [studying] satellite images.”

Mueller noted that since half of the ice shelf is still visible, the team is likely to set up shop elsewhere in the region.