I arrived in Russia in 1997, when Boris Berezovsky’s influence was at its height. The year before, he had managed to get Boris Yeltsin reelected, and we need not think too hard about how or why that was achieved. In those days Berezovsky was often in Chechnya, and I couldn’t keep up with how much stuff he owned. Then Putin became president, and shortly afterwards the “Godfather of the Kremlin” was out.

Sometime later I read a vehemently anti-Putin editorial in a major British newspaper, before such things were commonplace. Who wrote this? I wondered. And then I saw the byline:

Boris Berezovsky.

I was stunned. Hadn’t the editor done a quick web search before paying this “Russian businessman” to write his screed?

Evidently not, although I now understand that serial failure to grasp that not every opponent of Putin is a brave Solzhenitsyn is characteristic of the UK and US media. Last year, for instance, I watched a documentary on Khodorkovsky, and the filmmaker was baffled when Russians expressed contempt for the fallen billionaire.

As for Berezovsky, for years I wrote him off as an embittered crook until I read an interesting piece by Edward Limonov, written in his trademark broken English. The author turned opposition leader was recalling a very expensive bottle of cognac the exiled billionaire had sent him upon his release from prison on weapons smuggling charges in 2003:

I like Berezovsky more and more. Exiled, he looks noble. Berezovsky is a type of anxious, never-satisfied life-eater, of warrior, the person who lives by the energy of conflict. Abroad, in Great Britain, he is forced to exist without conflict, in order to preserve himself from a Russian prison. He wants badly to go out of that golden cage of London, again go to exciting life of conflicts in Russia. He is not interested in money. Money is only fuel to his conflicts.

A life-eater, fueled by the energy of conflict! That also describes Limonov, who used to ramble on about legalizing polygamy and teaching kids to use flame-throwers (before he became a semi-respectable Putin opponent in the eyes of David Frost et al.) In Berezovsky, he recognized some of his own characteristics. And now I saw the oligarch differently. He was a game-player, a man who delighted in his cleverness, in danger, and who exulted in the provocations he staged before the global media.

I recall footage I saw of Berezovsky talking to a group of Russophile English aristocrats about Putin. With what pleasure – and ease -- he seduced these political naifs, who were blind to the conspiratorial nature of Russian power. Even better was when he befriended George Bush’s hapless wee brother Neil, who in the mid 2000s was trying to sell a video projector he called “The Cow” as an educational tool to developing countries who didn’t know any better. Berezovsky got involved and made a few introductions in the former USSR, even accompanying the mini-Bush on a visit to Latvia. Putin was outraged; Berezovsky was delighted; Bush never sold his rubbish toy.

Berezovsky’s influence in exile reached its peak with the murder of his employee Alexander Litvinenko. Suddenly the renegade oligarch was at the center of the world’s attention, wreaking havoc upon Putin’s reputation. But this is also when journalists started looking seriously into the career of the life-eater, and his reputation never recovered either, for the “heroic dissident” was clearly a man enmeshed in plots, scandal, crime and death.

Berezovsky, of course, was an exceedingly clever man. Long before he was a car dealer, he was a mathematician and a member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. But this was his problem. His attitude was that of someone who had always considered himself the smartest man in the room. Now when the other man in the room was Yeltsin, that may have been true – but then again, the table at which Yeltsin sat also had more brains than the Russian president.

Yeltsin, it is clear, was too easy to manipulate – because after that Berezovsky serially underestimated his foes. Having backed the mid-level ex-KGB officer Putin as successor, he was astounded when he was driven into exile. He also underestimated his protégé Roman Abramovich, and this is where his intelligence really started to undermine him. You do not need to be a lawyer to know that Berezovsky’s claim that Abramovich bullied him into giving up his stake in Sibneft sounded feeble. Indeed, the case was so tenuous that Berezovsky must have used a lot of intellectual energy to persuade himself of his own arguments.

The results were disastrous, and with the evaporation of his money and influence, Berezovsky could see that the game was finally up. Or maybe not; when Putin’s spokesman claimed that Berezovsky had sent his foe a handwritten letter pleading to be allowed to return to Russia, I was skeptical. All exiles yearn for home, but did Berezovsky really think he could sweet-talk Putin? But then I remembered his arrogance, his hubris, and wondered if he hadn’t persuaded himself he could use his cleverness to pull off one last great act of gamesmanship…

And then, it would seem, he hanged himself.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and may not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.

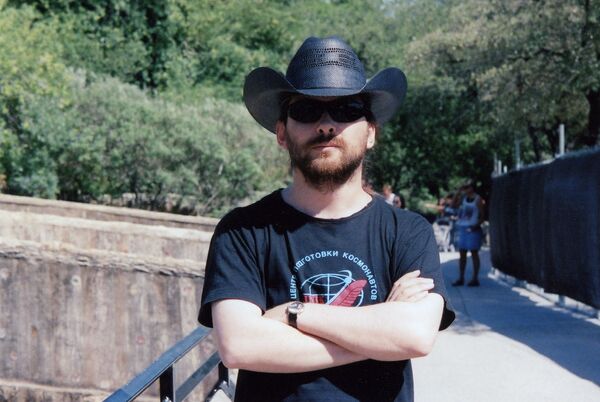

What does the world look like to a man stranded deep in the heart of Texas? Each week, Austin- based author Daniel Kalder writes about America, Russia and beyond from his position as an outsider inside the woefully - and willfully - misunderstood state he calls “the third cultural and economic center of the USA.”

Daniel Kalder is a Scotsman who lived in Russia for a decade before moving to Texas in 2006. He is the author of two books, Lost Cosmonaut (2006) and Strange Telescopes (2008), and writes for numerous publications including The Guardian, The Observer, The Times of London and The Spectator.

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Bolshoi Acid Attack: The Scandal Spreads

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Iran Is Not Very Good at Image Management

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Don’t Tear Down This Wall

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Who Are the Hair Police?

Transmissions from a Lone Star: I Rather Like the Taste of Horseflesh, Actually

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Ex-Popes, Politicians and Pensioner Rock Stars

Transmissions from a Lone Star: The Tower of Babble

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Of Iranian Monkeys and Other Real Life Space Invaders

Transmissions from a Lone Star: The Good Stalinist

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Celebrity Death Match: Andrei Tarkovsky vs. Lindsay Lohan