RussiaProfile.Org, an online publication providing in-depth analysis of business, politics, current affairs and culture in Russia, has published a new Special Report on the 20 Years since the Fall of the Soviet Union. The reports contains fourteen articles by both Russian and foreign contributors, who try to analyze the many changes that have taken place in Russian society since then and attempt to answer two perennial questions: was the collapse of the USSR the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century”, as Vladimir Putin once said, or a blessing for its people? And how far has present-day Russia departed from its Soviet past?

Soviet Names Still Survive in Modern Russia.

First names inspired by the October Revolution and its leaders appeared as a way of demonstrating commitment to the cause in the early years of the Soviet Union. Often acronyms of the initials of Soviet luminaries, revolutionary events or achievements, from the late 1910s onward children of the Soviet Union wore their parents’ political beliefs, aspirations or fears on their birth certificates. For the country’s orphans—often the children of disgraced enemies of the people—politicized names were a way to reinvent themselves as model Soviet citizens. Although the popularity of Soviet names peaked in the immediate aftermath of the revolution and living with such a name had its drawbacks, people continued to give their newborn children Soviet names into the 1980s—guaranteeing that this quirk of the Soviet Union will remain a small part of Russian life for many years to come.

The practice of naming newborn babies in honor of the revolution and its heroes first appeared in the late 1910s. In some cases, it reflected parents’ enthusiasm for the regime change and in others, their fears about how their past may be interpreted by the new authorities. It was fuelled by the Soviet authorities’ clampdown on bourgeois and Orthodox Christian traditions, which cast doubt on many previously popular names and encouraged parents to choose ones that reflected the new values.

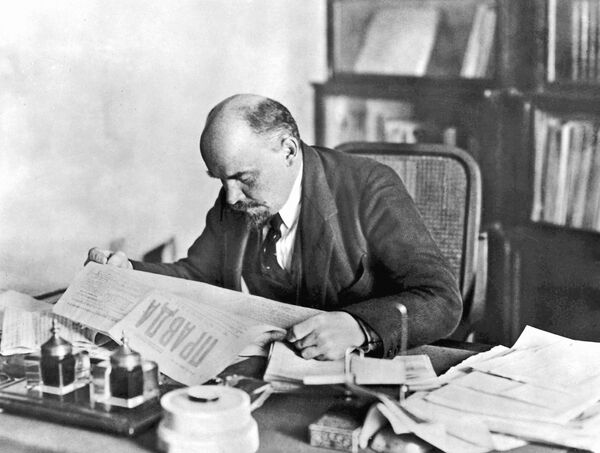

Some parents simply gave their children the first names of prominent people—Vladimir in honor of Lenin, for example, which was the most popular boy’s name in Moscow between 1924 and 1932. But others were explicit and easily recognizable tributes to Soviet heroes, with Lenin again leading the way. Boys’ names honoring the father of the revolution include: Vladlen (Vladimir Lenin), Vilor (Vladimir Ilich Lenin—organizer of the revolution), and Leninid (Lenin’s ideas), while girls were called Ninel (Lenin backwards) and Lenora (Lenin—our weapon). Names formed from the initials of a string of soviet heroes were also popular, such as Mels (Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin) and Melsor (Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, October Revolution).

In an interview with Ogonyok in May of 2005, Alexandra Superanskaya, co-author of “Russian Names” and Russia’s leading anthroponomy expert, described where some of these names came from. “On the corner of Kuznetsky Most Street and Neglinnaya Street there was a commission, which invented and registered new Soviet names. From 1924 to 1930 they issued calendars with recommendations. There you can find girls’ names, such as Electrification, and boys’ names like Tractor, as well as many others.”

Engelisa Pogarelova was born on August 5, 1934—the anniversary of her namesake Friedrich Engels’ death. “I think my parents wanted to give me an original name, something unusual,” she said. “Nobody else in my family had a Soviet name. My brother is called Valery and everyone else had normal Russian names.” Although Pogarelova said she has always been happy with her name, it has caused her a few small problems. “Many people make mistakes because I have an unusual name, they pronounce or spell it incorrectly. On all of my documents now it is spelled ‘Engilisa,’ not as it should be spelled, ‘Engyelisa.’”

She also felt that at times her name restricted her social life growing up, although she found ways to get around this. “I was sorry not to have a name day, everyone else had one as well as their birthday, but I didn’t have one. And then my birthday falls in the summer, when nobody is around, so I decided to do something about it and have another celebration on November 28—the date of Engels’ birth. I got a bit carried away then and decided to celebrate Marx’s birthday on May 5 as well, but that didn’t really take off.”

Pogarelova is the director of The Central House of Arts Workers (Tsedri). Always interested in the arts, she started her career working in cultural clubs attached to factories, designed to both entertain and educate the workers. This meant she had to take ideology courses at the university, where her name turned out to be a disadvantage. “At the Institute we had Marxist-Leninist Pedagogy and my teacher was horrible to me. He used to call me Marxisa and say ‘With a name like that, you don’t have the right to get less than five.’ So I had to work extra hard in that class and it was really boring—I was always more interested in creative subjects.”

But the confused response to her name has also kept her entertained over the years, with even those who worked alongside her sometimes making the odd Freudian slip. “Once when I was working as the director of one of the culture clubs my husband came to pick me up. He asked for the director and the woman on duty called out ‘Evangelisa Georgievna.’ When I came out he told me things had changed and I was now named after the Gospels!”

Name Dropping

By the 1950s some bearers of Soviet names had become prominent public figures, such as prima ballerina Ninel Kurgapkina and Vladlen Bakhnov, co-author of the script for the classic Soviet comedy “Ivan Vasilievich Changes Profession.” But most Soviet names did not take off and have since died out, if they ever existed, particularly the more creative ones, such as Pyachegod (the five year plan in four years), Pridespar (hello delegates of the party congress) and Smersh (death to spies).

Names easily identifiable with political figures who subsequently fell out of favor also struggled to survive. Those that venerated Stalin are a good example of this. After his death many men called Mels and Melsor dropped the “s” from their names, and girls named Stalina changed their names to alternatives that were not associated with the dictator. Pogarelova experienced this second hand. “There was a singer that I used to work with called Stalina. I’m not sure when exactly she changed her name, but by the 1970s, she was already called Polina. It was not hard to change your first name; you just had to send an application to the registry office. It was much harder to change your surname,” she said.

Pogarelova herself never considered changing her name. “My parents gave me this name and I respect their choice,” she said. “To some extent I wished I could change my surname more. For a long time I was in charge of the fire safety department, which with a surname like Pogarelova (derived from the Russian verb ‘to burn’) led to quite a lot of teasing from my colleagues.”

But not all Soviet names have died out, particularly those which are more flexible. Damir existed before the revolution, but was reinvented by the Soviets to mean “Hello world revolution!” This gave the bearer more flexibility—to acknowledge it as a Soviet name, a pre-revolutionary name, or both.

Alexei Dmitriev was born in 1986. Two of his classmates at school in St. Petersburg had Soviet names—Damir and Vladlen. But it wasn’t until the class was in eighth grade that they realized what the names meant. “We were told by some teacher that these names are synthetic. We were reading ‘Heart of a Dog’ by Mikhail Bulgakov. We didn’t think that you could just call a child whatever you wanted, when we understood that it was a normal thing in the Soviet Union we went through culture shock.”

Damir’s classmates had always just thought that Damir was a Tatar name. “But it’s both. His parents are Tatars, but they also wanted their son to have a Soviet name,” Dmitriev said, adding that Vladlen’s parents were teachers, who were perhaps slightly more committed communists than the average citizen. “I think his parents just liked Lenin. It was rather unusual to give the boy such a name when it had already gone out of fashion though,” he said, adding that Vladlen’s two brothers did not have Soviet names. Unlike Pogarelova, Damir and Vladlen were not happy with their names growing up. “Vladlen sounds girly and Damir sounds weird, so no, they did not like them,” Dmitriev said.

The novel, which first brought the students’ attention to Soviet names, Mikhail Bulgakov’s “Heart of a Dog,” reflects the reception these names received from some quarters when they were first introduced. In one scene bourgeois surgeon Filip Preobrazhensky is arguing with the dog he has successfully turned into a man about the name he has chosen—Poligraph Poligraphovich Sharikov: “‘Your name seemed a bit strange, it would be interesting to know where you found it?’‘The house committee gave me some advice. We looked at the calendar and I chose a name.’‘No name like that can be on any calendar.’ ‘That’s surprising,’ the man smiled, ‘When it’s on the one hanging in your consulting room.’ Without getting up, Filip Filipovich leaned over to the bell on the wall and Zina appeared. ‘Bring me the calendar from the consulting-room.’ After a pause Zina came back with the calendar and Filip Filipovich asked: ‘Where?’ ‘The name-day is March 4.’ ‘Show me… grrr.. damn. Throw this thing on the fire at once!’”

Fictional characters

“Heart of a Dog” marked the beginning of a minor trend in Soviet literature to use Soviet names to convey information about contemporary values, or the battle going on between those values in the Soviet Union. Andrei Platonov began writing his unfinished novel “Happy Moscow” in 1933, by which time Soviet names were an established part of life. In the opening pages the main character, Moscow Chestnova (derived from the adjective honest), who has been wandering the streets as an orphan and is unsure of her real name, is given a new one in a children’s home. “They gave her a first name to honor Moscow, a patronymic in memory of ‘Ivan’—the ordinary Red Army soldier fallen in battle, and a surname as a sign of the honesty of her heart, which had not yet become dishonest, although it had been unhappy for a long time.”

This trend in fiction also survived the collapse of the Soviet Union, as Viktor Pelevin gave a Soviet name to the central character of his novel “Generation P.” The book, which was written in 1999, deals with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the formation of a new Russian society, through the world of advertising, psychedelic drugs and the main character’s ideological and career progression. Vavilen Tatarsky is named after 1960s counterculture writer Vasily Aksyonov and Vladimir Lenin by his father: “Tatarsky’s father evidently could easily imagine that thanks to what he understood from Aksyonov’s uninhibited page, the eternal Leninist could grasp that Marxism had stood for free love from the beginning.”

Embarrassed by his name Tatarsky, starts to introduce himself as Vova, before pretending his father was in fact fascinated by Eastern mysticism and named him with the ancient city of Babylon in mind. “Despite this brilliant reinvention, at the age of 18 Tatarsky happily lost his first passport and his second one read Vladimir.”

While they may remain a convenient literary device, Soviet names are not popular among parents of Russian newborns today, who are overwhelmingly opting for traditional Orthodox or Slavic names. Evgenia Smirnova, a spokesperson for the Moscow Registry Office, said that three names have dominated in the capital over the last two decades. “Alexander is in a stable position at the top of the most popular list for boys. The rest of the top ten changes quite a lot, but Alexander has been the most popular for the last 20 years. For girls in the same period, Maria and Anastasia have shared the top spot, and in the last two years Maria has come out top.”

But there is evidence, albeit slight, that the idea behind the communist names—honoring a system, idea or hero in the naming of a child—has not completely died out. Among the legions of Sashas and Mashas born across Russia in 2011, one little girl born in Omsk, Siberia was given the curious name of Medmia—a combination of the first letters of the current president’s surname, first name and patronymic.