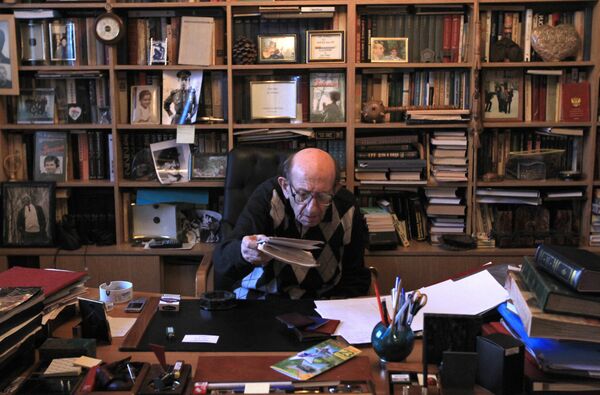

Russian Teacher and Principal Leonid Milgram Turns 90

Over the past month there were a series of celebrations in Moscow for the 90th anniversary of one of Russia’s most celebrated teachers – Leonid Milgram. De facto, he built and for more than 40 years, led one of Moscow’s best schools – School number 45. Hundreds of graduates, including celebrities and the country’s top education officials gathered for a gala celebration in a theater in central Moscow on February 25, while thousands of successful former students celebrated around the world: one look at “Milgram’s Children” group on Facebook is enough to realize how widespread this network is.

Milgram’s personality matters not only to his former students. There are ever fewer people around whose lives have encompassed the glory and horror of the 20th century to such an extent as his. Milgram is the son of a Polish Jew who became one of the Soviet Union’s first intelligence officers and then was arrested and executed as an “enemy of the people.” He is the son-in-law of one of the founders of the Italian Communist Party. He is a World War II veteran, representing the generation of men born in the early 1920s of whom only a few out of each hundred returned from the front. Today out of some 500 men of the heavy artillery squadron with which he went as far as Breslau, only eight survive. A historian by profession and a teacher by calling, Milgram himself is history. And talking to him is learning.

The Lucky Guy

“I went online today, and saw that the present life expectancy for men is 61 years,” said the 90-year-old elder. “I thought ‘Gosh, I am already 50 percent older than them!’ And if you consider all I went through, it increases my age, especially given my character.”

Milgram likes this game of counting one year for two or three, as was done to calculate retirement age for those who served in the Arctic and other far-flung areas in the Soviet Union. Milgram applies it to family life too – he and his wife Mirella have been together for 64 years, but they keep poking fun of each other by saying that judging by their tempers, it should be 128 years. Mirella is the daughter of a prominent Italian communist Ottavio Pastore, the first chief editor of l’Unita newspaper. Like Milgram, she grew up in the Comintern building on Gorky Street, then corresponded with him throughout the war and stayed in Moscow with the poor student and future school teacher when her father became a senator in post-war Italy.

Any conversation with Milgram will inevitably touch upon this building – the former Lux hotel, now Hotel Tsentralnaya under reconstruction on Tverskaya Street. This is his true home. “All general secretaries lived there, each in one room with a family. One kitchen per floor, one men’s room and one ladies’ room per floor. Quite limited living conditions. [Bulgarian communist leader Georgy] Dimitrov, [Yugoslav communist leader Iosip Broz] Tito, [Italian communist leader Palmiro] Togliatti, [German communist leader Wilhelm] Pieck, [Czech communist leader Klement] Gottwald, [Japanese and American communist] Sen Katayama lived there. All of them! They were very interesting folk. And then came 1936 and 1937.”

The years of the great terror, 1936 and 1937, always come up as a refrain in a conversation with Milgram. It happens when he starts remembering his house on Gorky Street and can’t recall what kind of monument stood nearby, on the site where as of the late 1940s there is a monument to the founder of Moscow Prince Yury Dolgoruky. “There was a monument to [late 19th century Russian national hero General Mikhail] Skobelev, then it was knocked down and instead they build the Liberty monument. In it, in the niches, there was the text of the first Soviet Constitution that was signed by members of the Presidium of the All Union Central Executive Committee. Then came 1936, and they began to take down the names. Ultimately, only the names of Sverdlov and Kalinin remained. It’s living history!”

Milgram’s first memory as a child was the arrest of his father in 1925 in Athens, where he was the Soviet intelligence station chief. “Then I served as a mail box – that is, the consular would take me for the prison visits while I had instructions in my pockets,” recalled Milgram. Facing him on his desk are two framed photos of a dandy wearing a morning suit and a top hat – Soviet consular in Shanghai Isidor Wolfovich Milgram. “My father had eight names and eight passports in different countries,” Milgram noted.

In 1937, when his father was arrested in Moscow, he hugged his son and said that he would definitely come back because he was not guilty of anything. He never came back. The step-mother followed him as a “member of the family of an enemy of the people.” The 16-year-old boy was supposed to end up at an orphanage, but a decent chekist saved him by obtaining a nine-square-meter room in a communal apartment for him. “He saved me from the orphanage,” Milgram said. When he finished high school, 12 out of about 50 students in his class had lost their parents to the GULAG.

Today Milgram is seriously concerned with the neo-Stalinist trend in Russia. “There was a television program the other day, in which people voted between a Stalinist and his opponent,” Milgram said. “The Stalinist won by a large margin. I was astonished and horrified,” he said. Why the tendency? Milgram explains it by a reaction to the asocial character of the modern Russian state. “Frankly I am scared by the direction of our state development, by how asocial it is. The first law in Italy after the fall of Fascism was to ban currency exports. And what’s with us? The gap between the rich and the poor is terrifying. When perestroika began, I placed my bets on the intelligentsia. But one type of intelligentsia – people with a great conscience – left this world. And the ones who did not pass the temptation with money and power raised their heads. And that is scary.”

On the eve of the 65th anniversary of the victory in World War II the issue was broached of whether portraits of Stalin and Marshal Georgy Zhukov should be placed around the city. Milgram resolutely spoke out against it at a veterans’ meeting. After that he was no longer invited to such meetings.

But despite all the politics, the war was undoubtedly a central event in Milgram’s life. “I am a lucky guy. In 1939 all the first-year university students were mobilized into the army. They did not take me because of my father. I wrote letters twice to the Defense Commissar Voroshilov and eventually they took me. I ended up in a division that was made up of Donetsk miners plus two other contingents – students like myself and officers from two artillery academies – in Leningrad and Odessa. They were real military intellectuals. There was such an incredible human relationship in the division! Strange to say it, but we did not curse! People didn’t drink alcohol! Later on I had my “coat of arms” hanging in my principal’s office – the stick and the carrot. That’s something I brought from the army. Until hazing got out of hand I always told my boys that they should go to the army, that they will grow into men there. And in the recent years, when boys started returning from the army, I realized that it is no longer that way.”

After the war Milgram finished his studies at the history department of the Moscow State University and was sent to work as a teacher to the northern city of Arkhangelsk. In 1959 he became the vice-principal and in 1960 – the principal of School number 106, which was later renamed into School number 45. “We had several schools which produced intellectuals,” said Milgram. “But I had another task. I wanted the kids to become not just intellectuals, but intellectuals with other qualities at the bottom of their hearts – decency, kindness, knowing how to live not just for themselves, but for society. In other words, we graduated what is known as the intelligentsia. And now I revel in it! I received hundreds of letters for my birthday, fantastic letters! One former student wrote to me that the school of course gave knowledge, but it was not the main thing. The most important thing was that it was a school of humanism and that we were brought up to be free.”

Humanist Methods

How could he achieve this, especially in the closed environment of the Soviet Union? Milgram names only one method: the selection of teachers. Every one of them had to be not just a professional in his subject, but an impressive personality and a friend for the students. An interesting situation emerged: both Milgram and other teachers were, on the one hand, unquestionable authorities for the students, and on the other hand – approachable advisors. “Any girl could come, if necessary, and cry on the teacher’s shoulder,” says Milgram. “And the caricatures of teachers that hung in the hall on the first floor? Where else could you see that? We had it and it broke the wall between teachers and students.”

Another method was patronage. In the Soviet times, it was patronage over war veterans. In the post-perestroika period there was patronage over an orphanage for children with cerebral paralysis. “Of course, it is important for those who are being served,” said Milgram. “But it is even more important for those who are serving. During their school years children have to go through volunteer activity. It is very important. At the university level, they can choose a political or religious organization. Children’s organizations, though, must not be political.”

At the same time, there was always strict order and an attempt at preserving equality at the privileged school, where there has always been a “parents’ competition” to enter. Everybody remembers how Milgram insisted on a uniform for the students, how he pleaded with parents not to buy expensive pens for their children, how he gave money to unkempt students for a haircut, or how he would stare down schoolgirls wearing ear rings until they took them off with shaking hands. He claims that he had whipped students once or twice. No one has seen that, of course.

Speaking of his pedagogical methods, the communist, Milgram, who later realized he was socialist, doesn’t shy away from pastoral vocabulary. “I had such a method – when some student would do something badly wrong, I’d summon him to my office, give him a notebook and say: write a confession about how you reached such a low in your life,” he recalled. “And once the Moscow city superintendant came, and there was an episode that shocked her: All of a sudden, one of our girls rushed in, wearing a wedding dress, straight from the ceremony. She came to ask for my blessing.”

Thinking Versus Non-Thinking

Does Milgram follow today’s debates about education reform? Yes, he does. “Some things scare me,” he said. “But there are good things too. They don’t really pay attention to the upbringing of students, rather than simply informing them; they just proclaim the slogans about values. In the meantime, human values are of the utmost importance. The new course ‘Russia in the World’ includes a part on ‘combating the falsification of history.’ But it’s on such shaky ground it is bound to do exactly the opposite – falsify history. There are textbooks that simply praise Stalinism!”

As far as the reduction of the number of subjects and lessons is concerned, the details can be discussed and adjusted, Milgram believes. As is the individual coursework for students, which School number 45 had as of 10th grade. The key word in his discussion of educational reform is “choice.” “The education system has to function like a pyramid,” he said. “You have to weed out the not-so-talented students. But there is a big problem here. I am convinced that already in the seventh grade there should be many optional courses, so that children can orient themselves and make a choice about their future career. The standardized tests should be amended. There should be choices in the types of exams as well. For example, there should be a choice of whether to write an essay or a summary. If a student picks to write a summary, he limits himself to factual knowledge. If he writes an essay, he can think independently. The same option should be offered in mathematics and in other subjects – the choice between thinking and non-thinking students. There should be specialized classes. And if the present capacities are not enough, 12th grade should be introduced. Various models should be tested.”

But in a conversation about education, the 90-year-old teacher speaks more about values. “I revel in what I have grown,” he said. “When the borders were opened in the late 1980s, I called my former students and told them: ‘Hey, rascals, the teachers cannot afford to travel abroad!’ The former students brought money to travel agencies and we formed three groups, and the teachers went off to different countries.” Then the “rascals” funded a second pension for teachers who had worked for more than 25 years at School number 45. And an envelope with money, which a graduate once left on the table on Milgram’s birthday, eventually turned into an annual present on Victory Day to the veterans of his artillery division. “It is amazing!” Milgram said. “That’s what keeps me going!”

“I Revel in What I Have Grown”

© RIA Novosti . Valery Melnikov

/ Subscribe

Over the past month there were a series of celebrations in Moscow for the 90th anniversary of one of Russia’s most celebrated teachers – Leonid Milgram. De facto, he built and for more than 40 years, led one of Moscow’s best schools – School number 45. Hundreds of graduates gathered for a gala celebration in a theater in central Moscow on February 25, while thousands of successful former students celebrated around the world: one look at “Milgram’s Children” group on Facebook is enough to realize how widespread this network is.