RussiaProfile.Org, an online publication providing in-depth analysis of business, politics, current affairs and culture in Russia, has published a new Special Report on the 20 Years since the Fall of the Soviet Union. The reports contains fourteen articles by both Russian and foreign contributors, who try to analyze the many changes that have taken place in Russian society since then and attempt to answer two perennial questions: was the collapse of the USSR the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century”, as Vladimir Putin once said, or a blessing for its people? And how far has present-day Russia departed from its Soviet past?

Russian Historians Have Discovered a New Appreciation for Soviet History.

There are whole spheres of Russian cultural life that undergo a period of decline, but the Soviet period is a pleasant exception. The thousands of books, tens of thousands of newspaper stories and millions of comments on the Internet are a reflection of the passions that still rage around the 74 years of Soviet history. Some even see all sorts of conspiracy theories behind this. “Interest in the past is being artificially pumped up by certain groups inside the ruling elite,” blogger Alexander Baurov wrote on the Internet site www.liberty.ru, one of controversial spin doctor Gleb Pavlovsky’s projects. “The share of historical discussions is disproportionally high in our political discourse. Certain groups inside the ruling elite, despite calling for civil reconciliation, support marginal groups of pseudo-scientists. These pseudo-scientists try to make people believe that their history is a bundle of blood and dirt. The subtext is that people with such a history are only worthy of being a fertilizer for the 20 years of ‘flourishing liberalism’ that Russia went through between 1991 and 2011.”

So much for the “liberal conspiracy” theory. The conspiracy theory that sees “creeping Stalinism” behind the unending flow of new books on that epoch is even more widespread. Its main hotbeds are the Memorial Society and the bureaus of foreign newspapers in Moscow, as well as several Russian liberal media outlets. The clichés of this theory are well known: Vladimir Putin, a former KGB officer, is seen as a “new Stalin” and memories of the Soviet past are deliberately romanticized.

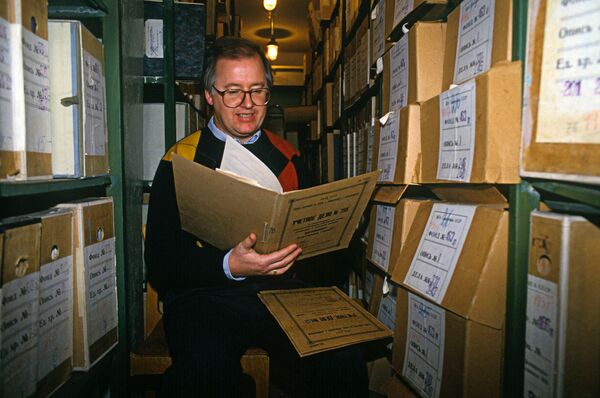

Professionals are somehow less inclined to see politics and conspiracies behind these trends. For Yuri Borisyonok, the editor in chief of the Rodina historical magazine and a professional archive researcher, the interest in Soviet history is a reflection of new opportunities for researchers. “The interest in the Soviet period is quite understandable, since now you have a variety of sources available. Besides, there is a niche to be filled, because this period had not been properly studied for decades before the late 1980s,” Borisyonok said. “Before Mikhail Gorbachev, the 20th century was not a fashionable area of research for young Russian historians. The 19th century was seen as a lot more intellectually challenging and glitzy, with its aristocracy, great literature and intellectual debates. The reason for this ostracizing of the more recent history was not a lack of drama, but a lack of sources and political pressure. So, the 20th century was left to mediocre students, who limited themselves to ‘safe’ topics and spent their lives writing about, say, the heroic labor of Soviet boot-makers in the days of the Great Patriotic War. So when restrictions on the Soviet period were lifted, there weren’t enough professionals, and lots of amateurs suddenly became historians—with all the ensuing consequences.”

Borisyonok rejects the widely-held belief that there is not enough archive material available. “There are a lot of things you can find in the archives. And there is tons of information already published in books, newspapers or on the Internet. However, the way people process this information in some recent publications leaves much to be desired,” he said. “Under the Soviet Union, texts went through a lot of filters before going to press. The works of historians then went through numerous academic councils, verification commissions and, finally, the censors themselves. This is not the case now, and this fact has both positive and negative consequences. People write what they think, but numerous mistakes and absurdities sneak into their texts.”

Power to the written word

Of course, freedom gave birth to all sorts of things, including some very bad ones. The biggest scandals have broken out around history textbooks, because they involve both state money and mandatory reading. The two most notorious cases were the school textbook on Russian 20th century history by Igor Dolutsky and “History of Russia: 1917–2009,” a textbook for university students written by Alexander Vdovin and Alexander Barsenkov.

Dolutsky, a staunch liberal who said in an interview that there was “nothing to be proud of in Soviet history,” included in his textbook a quote from liberal politician Grigory Yavlinsky, who described Russia in the years of Putin’s presidency as “an authoritarian police regime.” Barsenkov and Vdovin, who are on the nationalist side of the political spectrum, were accused of anti-Semitism in their text. Without making outright anti-Semitic statements, the two authors returned to the “Jewish theme” in their 800-page long book several times, providing lengthy and unverifiable statistics on the proportion of Jews in various government institutions in the Soviet Union. At one point, Barsenkov and Vdovin made vague hints that the Jewish victims of Stalin’s repressions were somehow connected to U. S. interests and that the infamous Stalinist campaign against “rootless cosmopolitans” was a reaction to American “hegemony.”

In both cases, the textbooks were not banned. They were just no longer recommended to teachers working in both schools and universities. Thousands of books and print editions with much more radical views continue to be sold at bookstores. “The fact that the authorities only reacted to my textbook, which mentioned the current top officials in the country by name, shows how little attention they paid to history education in this country,” Dolutsky explained. “Boris Yeltsin, who ruled Russia for ten years, just did not pay any attention to history education at school at all. Any man from the street could write a school textbook then.”

In fact, the official who first expressed indignation at Dolutsky’s book was none other than Mikhail Kasyanov, Russia’s prime minister from 2000 to 2003, now a leader of the unregistered Party of People’s Freedom (PARNAS). “We may have to go through this period, when all sorts of amateur publications flood the market,” said Andrei Turkov, a veteran Russian literary critic. “For too many years, we had one officially registered view on every subject—not only in history, but also in, say, literature. [Famous prose writer Nikolai] Gogol was a satirist, and nothing else, Alexander Pushkin was an independent free-thinker, and nothing more. But they were both also Orthodox Christian believers! So now, after many years of neglect, the Christian character of Gogol’s writings is studied by a whole new school of specialists. This does not mean that we should forget Gogol the satirist. Life was always complicated—in the Soviet times and before. Let’s look at all sides of it.”