RussiaProfile.Org, an online publication providing in-depth analysis of business, politics, current affairs and culture in Russia, has published a new Special Report on the 20 Years since the Fall of the Soviet Union. The reports contains fourteen articles by both Russian and foreign contributors, who try to analyze the many changes that have taken place in Russian society since then and attempt to answer two perennial questions: was the collapse of the USSR the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century”, as Vladimir Putin once said, or a blessing for its people? And how far has present-day Russia departed from its Soviet past?

Many Young Russians Are Nostalgic for the Soviet Union.

Contrary to popular belief, the tight grip that 70 years of Soviet indoctrination exerted on the popular psyche was not limited to the older generations of Soviet citizens. Many of today’s young people—who were not even born when the Soviet Union still existed—are showing symptoms of grief and pining for the “good old days.” While experts continue to unravel the mystery behind ex-Soviet citizens’ love for the good old former union, more and more young people say they too are casting some nostalgic looks at the Soviet past.

For many young people, the fabled social guarantees and safety net that the Soviet regime provided were the keys to their hearts. “It was good that the government provided people with the necessary living conditions and social benefits, there was more confidence about tomorrow,” 20-year-old Maria Skorik, who studies PR at the Journalism and Philology Faculty of the Southern Federal University in Rostov-on-Don, said. For her, social welfare is what was cool about the Soviet Union, even though she said that her idea of those times was based on bedside stories.

Maxim Rudnev, aged 23, who studies at Russia’s Academy of Law and Governance, also said recreational storytelling by his parents formed his opinions about the Soviet past. “My opinion is based on stories I was told by my grandparents and good Soviet movies,” said Rudnev, who was born in East Berlin and never lived in the Soviet Union. “For me, the Soviet past is associated with victories in World War II, the achievements of the space programs, science and the labor movements, such as Stakhanovism.” Rudnev is now one of the patriotic young fellows in the pro-Kremlin Molodaya Gvardiya political movement, which, among other things, groom the young generation to look at the Soviet past with admiration and some veneration.

Through rose-colored glasses

A recent study by Valeria Kasamara and Anna Sorokina at the Laboratory for Political Research at the Higher School of Economics found that nostalgia for the Soviet past is still quite common among Russians, including the younger generation. The study, which polled 300 high-school and university students aged between 13 and 32, found that young people with little or no memory of the Soviet Union also tend to be nostalgic for the past. “Young Russians didn’t live in the Soviet Union and only know about it from stories they have been told by their parents, grandparents and teachers, or Soviet movies,” Kasamara said. “These tend to concentrate on positive experiences and don’t reflect the gloomy Soviet reality.”

Sorokina added that those who remember the Soviet Union tend to focus on its achievements.

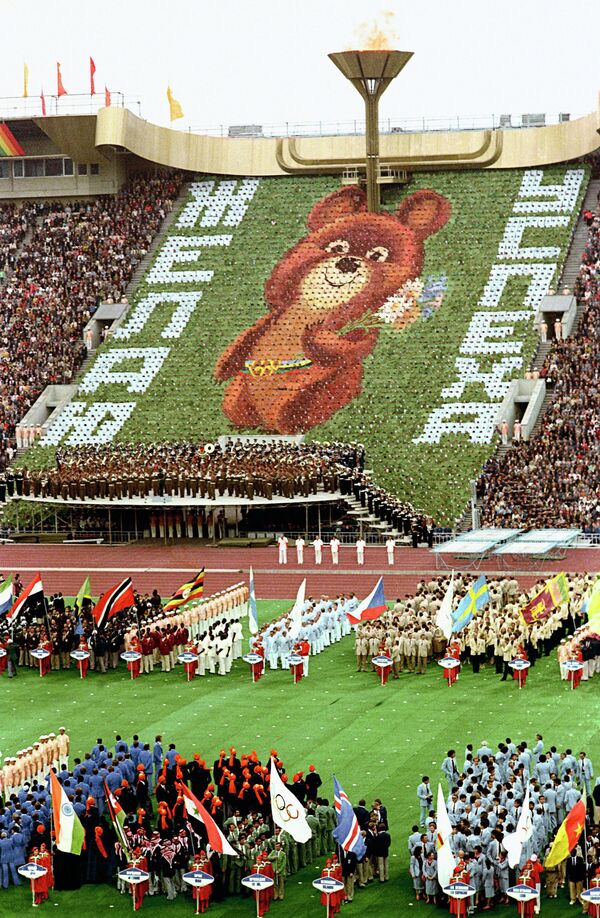

“To appeal to teenagers, parents only reminisce about the Soviet achievements and the positive side, and try to compare today with the past within an alluring context. For instance, the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow is compared with the 2014 Winter Olympic Games in Sochi and the Nashi political movement is compared with the Pioneers and Little Octobrists,” she said.

The degree to which people are willing to idealize the past, experts say, depends to a large extent on their social status, upbringing, education and movies. Tough social and economic conditions since the collapse of the Soviet Union can also lead people to idealize the past, according to experts. “The difficulties people faced after the collapse of the Soviet Union, including the 1998 economic crisis, the threat of terrorism, and the collapse of order—which had been so typical of the post-Soviet era, outweighed the problems of the Soviet period,” Kasamara said. “Although Soviet citizens didn’t like the gloomy Soviet reality, when shock therapy was implemented in response to the collapse of the Soviet Union people started to recall ‘the romantic and still air of the Soviet Union’ when they had government support and confidence about tomorrow.”

Such a line of thinking is also winning over young Russians, many of whom, Kasamara said, suffer from a lack of confidence and a sense that they are dependent on circumstances. “If somebody is not confident, has low self-esteem and is reliant on government support alone, they want to shift responsibility onto somebody else,” Kasamara said. For many, the social welfare or state guarantees that they will find a job after graduation are essential, because they are unable to act independently, she said.

Among the younger generation, students from regional and second-tier universities are more likely to suffer from post-Soviet nostalgia. “Students from top Moscow universities are more confident about their future, more open-minded, self-reliant and ready to suggest a compromise because they are in demand among employers,” Kasamara said.

But not all students fit in with this broad categorization, particularly when it comes to perceptions of certain aspects of the Soviet Union. Skorik claimed not to suffer from post-Soviet nostalgia at all, despite her positive impression of the Soviet welfare system. “I was born before the collapse of the Soviet Union, but I don’t remember this period,” she said, “I did not belong to Soviet society like I do not belong to American society, because I live in modern Russia. It’s my aquarium and I don’t want to live outside of it.”

Longing for a strong hand

The researchers from the Higher School of Economics believe that to some extent, post-Soviet nostalgia is symptomatic of a yearning for the strong and influential rule that characterized Soviet power. “Reliance on a strong government and leader helps to boost a person’s ego,” Kasamara said. “The grandeur and influence of Soviet power is what they are proud of, not great literature and scientific achievements. While Americans take pride in their freedoms, the average Russian is yearning for a strong and controlling government.”

This desire for strong leadership is also noticeable among young people who claim not to feel nostalgia for the past. Skorik sees a strong government as much more important for Russia than a close relationship with the West. While supporting friendly ties with other countries, she thinks that national interest and security should remain top priorities. “Concessions that may result in negative consequences for the country are not always a good way to deal with geopolitical problems,” she said.

Suspicion toward Western countries is also quite common among the post-Soviet generation, which Kasamara believes indicates it is yearning for the Soviet Union’s influence in the international political arena. A poll conducted by the Levada Center in 2011 revealed that 70 percent of respondents believe that Russia has a lot of strategic rivals and enemies abroad.

Rudnev also supports a strong government, but does not rule out the possibility of mutual understanding and collaboration. “Russia should work on building friendly partnerships with the West, but, concurrently, we should be prudent and avoid manipulation. In other words, we should be an equal partner for the West, but not a second-rate one.”

But young people’s perceptions of the Soviet Union are far from overwhelmingly positive today. Although he feels nostalgia toward Soviet grandeur, power and the country’s achievements, Rudnev would not like to live in the Soviet Union. He describes himself as a representative of a new generation that is focused on improving today’s Russia, not the past. “Try to make your own contributions to Russia’s development and wellbeing before asking something from the government, that’s my principle,” Rudnev said. “And this makes me different from Soviet generations.” Rudnev also believes that the lack of competitiveness as well as reliance on the government and social welfare hampered the development of Soviet society on both international and domestic levels.

Other young people, such as Skorik take a negative view of the uniformity that pervaded the Soviet Union. Her view is shared by 22-year old Aznavur Dustmamotov, who was born in the Soviet Union and immigrated to the United States in 2007 to study at Harvard. “The thing I most dislike about the Soviet Union is its uniformity. There was one official ideology, one path to success, even one taste in music, clothes, and film,” he said. Despite having a negative opinion of the Soviet Union, Dustmamontov said “it would certainly be curious to live there for a short time to witness such a radically different society.”

Dustmamotov, who described the Soviet Union as “a doomed experiment” and “a failed state, based on coercion and false social theory,” also believes there is a fine line between pursuing national interests and reclaiming imperial ambitions. He personally never felt part of Soviet achievements, even though he grew up in the Yaroslavl Region, because he is not an ethnic Russian. “I was always treated as an outsider, and I simply cannot identify with Soviet achievements, such as victory in World War II or the creation of the thermonuclear bomb, in the same way ethnic Russians do. I was always told, ‘This is our success, not yours.’ Whatever the greatness of the Soviet Union may have consisted of, I have no share in it and do not feel sentimental about it.”

Reinhard Krumm, the head of the Moscow bureau of the Friedrich Ebert Fund, an influential German organization promoting democratic values in Russia, is skeptical of how widespread post-Soviet nostalgia is among young Russians. “I have been teaching Russian students and I haven’t noticed that they want to go back to the Soviet Union. They have a lot of opportunities to study wherever and whatever they want. But whether Russian youth feels nostalgia toward the Soviet Union primarily depends on their level of education and social status,” Krumm said, adding that those who are better educated are more confident and more comfortable in modern Russia and feel less nostalgia for the Soviet Union.

An expert on Soviet and post-Soviet history, Krumm said that in contrast to their Soviet predecessors, consumerism and attachment to Western culture are characteristic of the current generation. “Now young people understand they will not be able to profit in an isolated society. In a globalized world Russians don’t want to stand apart, they want to participate.”

Krumm also believes that the post-Soviet generation differs in its perception of ideas of freedom, pluralism and responsibility. He said that European countries make certain distinctions between Soviet and post-Soviet generations partly because of this. “There is a lot of sympathy toward the new generation. It’s more open-minded and confident. Russian youth is the same as youth is in the rest of the world.”